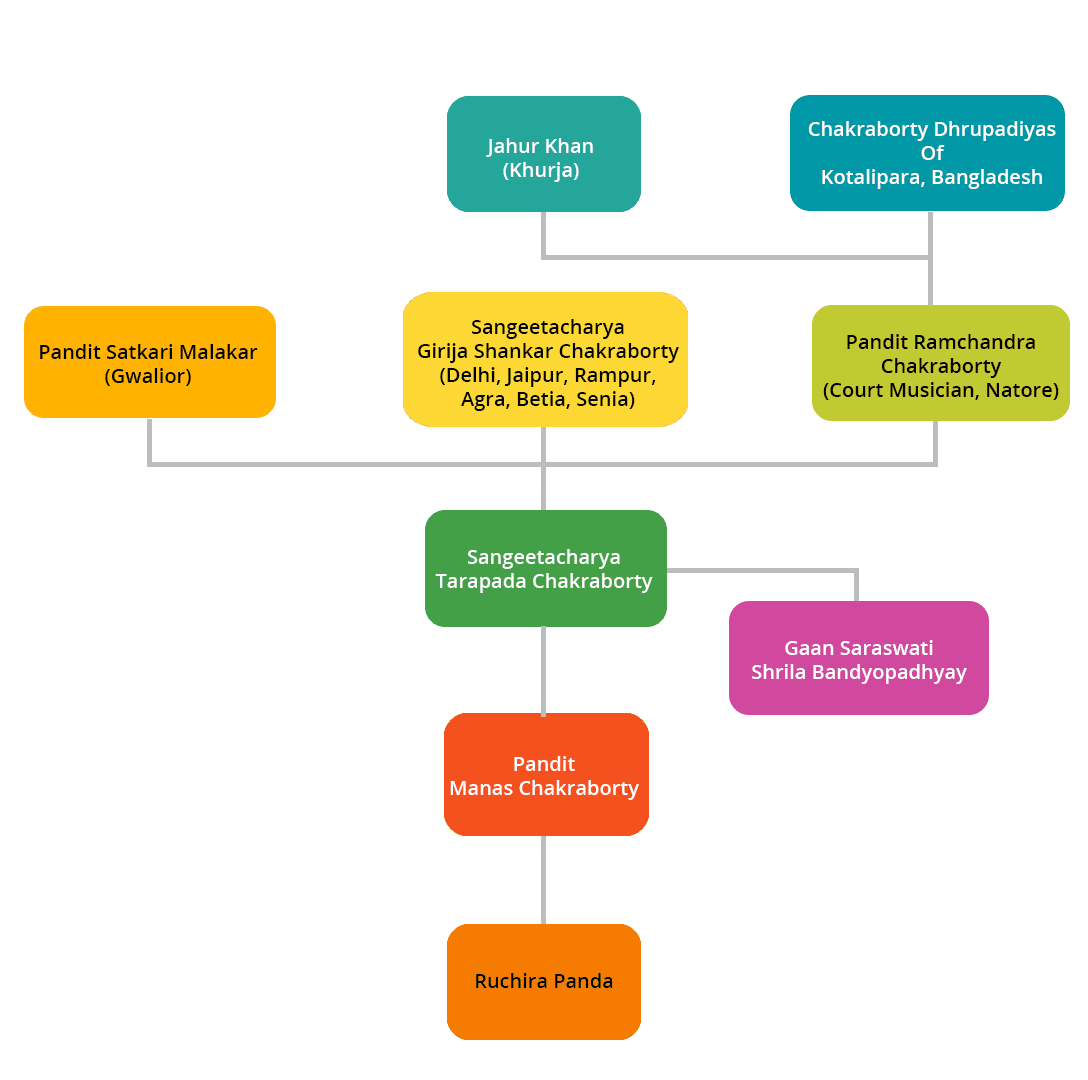

Kotali Gharana

Kotalipara in the Faridpur Zilla of East Bengal (presently Bangladesh) owes its origin to “Chandraburmankot”, erected circa 315 AD, the remains of which are still extant. “Kot” stands for fort, “Ali” signifies “wall and area surrounding the fort”, and “para” means a settlement or “a neighbourhood”.

KotaliPara had been a hotbed of intellectual excellence for ages, especially in music, art and scholarship. Some of the famous products of the soil include the painter Jogen Chowdhury.

The soil maketh the song. This gharana, therefore, carries a strong undercurrent of literature and fine arts. The major practitioners of the gharana, apart from their musical preoccupation, have displayed independent scholarship, an affinity to draw and paint and sculpt. A streak of independent thought has ensured an intellectual space more aligned with the famed Bengali finesse than allegiance to any orthodox mainstream gharana, though a clever “pick-and-choose” policy has seen to it that their goodies have been appropriated and Kotalified.

That’s why a Kotali bandish sounds intellectually so engaging and musical. The striking melodic arcs which form its signature, the mannerism and gimmick-free presentation, the complexity of the taans, the unexpected detour along the well-trodden Raga-road – those “aha” moments define some ephemeral attributes which can’t be easily analyzed into a frame of musical reference but try we must.

The first obvious characteristic is the spontaneous creativity on and offstage. A full bandish can be started with just the first two words being settled before the curtain goes up, and the rest will be filled up on the fly, with a matching melodic line developing in sync. The base expectation is that an interesting concert will need a new, suitably decked up Bandish based on the time and location and mood. Whether an ati-vilambit khayal or a thumri, this is a world of always-on-your-feet journey of the seeker.

The second aspect is the delivery. Mijaz is the king here. Falsetto is considered taboo and a soft mellow voice will not find many takers in this house. Bandish Gayan, the depiction of the drama in the lyrics with full-on emotional involvement but sans maudlin sentimentality, is key.

The talim from several gharanas in the past has resulted in the ability to change the style and adopt the core spirit of another gharana – and sing a stock Kirana Gharana Raga like Shudh Kalyan in a meend-heavy style. Bihagada,

The third aspect is the Bandish body – the quartet of lyrics, structure, scanning and melody. Apart from a few carefully curated ones, most traditional bandishes of various gharanas, have been found wanting in intellectual merit, and better substitutes have been invented.

The Kotali people are very touchy about the literary merit of a khayal or thumri in terms of form, content and abstractions – hence lines like

“Raat bhar sitaron ke dukh jwalan” or the

Jhinjhit Bada (Ati-Vilambit) Khayal

“Kahan jate ho ita andhiyar uta samundar dustar apaar” or Bihag Madhyalaya Khayal

“Aao paas piya baitho jatan kar

Ek do baat karun ji bhar ke”

Chhar de, main jaungi

Sakhi ata raha,

Dhoop char gayi

Vrindabani Sarang

Sarang ban ban mein

Pyasi firat ho

Sab drum patar sukha pade jo

The fourth aspect is philosophical. Kotali gharana, for many decades, has been in the hands of objective, rational intellectuals with a sense of humanism, an internal spirituality and zero religiosity. This is reflected in the somewhat lack of bhajans or religiously themed khayals – the mainstay of mass appeal of many classical musicians of other gharanas. So while Pandit Manas Chakraborty did allow students to do Saraswati Puja at his home, it had to be a twelve minute affair, while a published 12 minute track of his in Raga Saraswati played in the background. The puja day otherwise was a huge celebration, a pretext to hold day long classical performances where many senior and some junior artists would perform.

On a practical side, this lack of religious incentives means that the huge temple circuit in India and abroad, that in the days of yore was the birthplace of Indian Classical, and where other artists today happily offer their art for free or a pittance, has remained incongruous from the Kotali perspective.

The Kotali concert therefore, typically ends with a Thumri or Bangla RagPradhan and not a bhajan. On rare occasions, a nirguni bhajan would be sung, or a Durga Bandish created at the request a student in Raga Durga, but only as an exception. In some bandishes Shyam or Radha have been used, but only as literary/historical constructs.

The fifth element in this comparative analysis is centered around the lived life and simplicity. A Kotali musician worth his or her salt would frequent the world of libraries, natural history museums, art galleries, lit meets, and is expected to be versed in Tagore, Sacks, Dawkins, Monet, Ramkinkar and their ilk.

Being publicity, and politicking averse, to the point of being a recluse, is a trait that runs through the gharana.

Last but not the least, are the structural or elemental factors that a listener might look for. Kotali is the only gharana where chords are liberally used on the Harmonium, especially in Thumri. [ Excerpted ]